The Civil-Military Divide from a Soldier’s Foxhole

Captain Chris Chavez

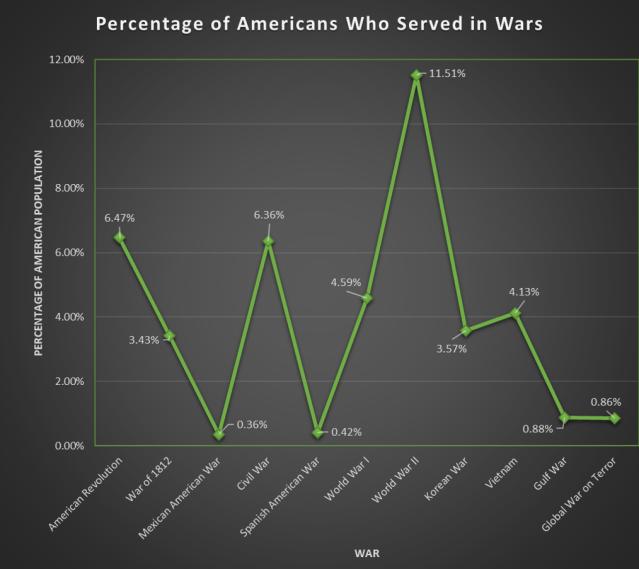

After nearly two decades of continuous combat operations in Afghanistan, the chasm between those who have served (including the families we leave at home), and those who haven’t served has continued to expand. Immediately after the September 11, 2001 terror attacks on the World Trade Center, The Pentagon, and Pennsylvania the war was new; whether people agreed with it or not, the war was a new shiny object that attracted everyone’s attention. As the war approaches its eighteenth year, its luster has dulled, and with it, the country’s focus. Compounding the problem, only 0.8% of Americans have served in the current conflict. With the disparity in numbers, the lack of attention on the war, and an increasingly divisive political environment has caused the two populations to be more isolated. However, with more meaningful communication, the two populations can bring themselves closer together.

The number disparity between veterans and the general population is not a unique phenomenon to the Global War on Terror generation. What is unique however, is the extraordinarily low numbers when compared to other conflicts. Only the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 and the Spanish-American War of 1898 are lower, with 0.36% and 0.42% respectively having served in those conflicts. Both of these wars were smaller in scope and much shorter in duration. This year, the Afghanistan campaign turns 18, and its supporting operations span many countries throughout the Middle East and beyond. Additionally, the benefits earned through military service, such as healthcare, tuition assistance, and the Post-9/11 GI Bill, make joining the military a much more lucrative venture for young Americans. Even with these benefits and increased opportunities to serve, the 0.8% figure is troubling.

From a veteran’s point of view, we have felt increasingly isolated as the war continues. Much of this isolation is self-imposed, and almost entirely emotional in nature. There will be those who know what the concussion of a sudden and unexpected explosion feels like and those who don’t. There will be those who can be awake in a split-second because the “incoming” alarm is sounding, and those who don’t. There will be those who constantly scan the sides of the roadways for hidden explosives and those who don’t understand why our eyes dart back and forth while we drive down the streets on which we played as children. There will be those who know what it feels like to lose a comrade who was more family than most blood relatives, to stare at an empty cot in the corner of the room once occupied by that friend hours before, and those who have never had to experience sudden, violent loss. However, in the back of my mind I know I cannot fault people for not experiencing these things. They are scars on my psyche that will never fade; yet I still can’t help but feel distant from those who do not share my experiences.

These emotions have been a significant source of cognitive dissonance for me personally, and I know that I am not alone in feeling this way. We have an all-volunteer force, meaning that we in the military serve to ensure that those back home do not have to experience how ugly the world can be. We go to the terrible places so that those at home can continue to live their lives in the manner they see fit. It’s a good thing that the average American doesn’t have to be hyper-vigilant on his way to his office job. That is success in our line of work, not failure. I know that to be true, but even still, relating to someone who has served, no matter when, where, or in what capacity the individual served, is easier than with someone who has not put on a uniform. Even as I write this, I begin to understand that I am personally responsible for helping widen the divide. By serving to protect the “American way of life,” I seem to feel distant from those who haven’t sacrificed for that for that ideal. As I re-read this paragraph, something inside me is screaming that I am wrong for having these thoughts, and I feel guilty for expressing them. Many veterans with whom I have spoken have expressed similar sentiments. With this internal struggle explained, what can be done to close this gap? Veterans and civilians alike have roles to play in bringing us closer together.

Perhaps if some things are cleared up, at least from my point of view, the rift can be in some way be made smaller. To those who haven’t served: while it’s good to show appreciation for someone’s military service, it is also important to note that paying $1.50 for a yellow ribbon magnet to put on your gas-guzzling SUV isn’t how you do it. Proclaiming “support the troops” in speeches and invoking the names of those who serve for personal gain is not how you show your support. Real support goes much further than these empty measures. Showing appreciation isn’t words or acts done for public consumption; it’s giving something back to those who are willing to give everything. There is a myriad of things you can do to show real and meaningful support. If you know a person in uniform, ask them if they have any friends who don’t get mail. Send care packages to units that are forward-deployed. Research and give to a military-focused charity. These are examples of things that mean the most to us. A bag of jerky is not simply a snack; it’s a little piece of home (and thus civilization) in a far-away land. Another thing civilians can do in passing, which has no monetary cost at all, is to simply ask questions of servicemembers. Ask them what they do and what it’s like to serve. I have often gotten the feeling that people are afraid to ask, for fear of conjuring up some sort of psychological demon or awkward story about the horrors of combat. However, the simple act of trying to gain some understanding of the military life is a wonderful way to show servicemembers and veterans that you care. Ultimately, giving of oneself, whether in the form of money or time, is far more meaningful to current and former military members than superficial lip-service.

I spoke at length of a famous instance of this self-giving in the last sermon I delivered, and the story bears repeating. Elizabeth Laird was known military-wide, because she was always at the Fort Hood air terminal when units were getting ready to fly to the warzone or when they were coming home. She would hug every single soldier before they got on the plane or as they disembarked. An article written shortly after her death in 2015 said she gave out about 500,000 hugs since 2003. Many of the soldiers she hugged still have the Psalm 91 card that she handed them. When she was in the hospital, many soldiers visited her to return the hug she gave them in their time of need, some coming from as far away as New York to sit and talk with her. The line at her hospital room was so long that the hospital staff had to sometimes turn people away. “I did not do this to be recognized,” she said from her hospital bed. “My hugs tell the soldiers that I appreciate what they’re doing for us.” She gave of herself. I don’t know what kind of financial burden she bore for her efforts, nor do I know how much time she spent in the air terminal, but the half-million hugs she gave made an indelible mark on many of the men and women she embraced.

Ms. Laird’s statement about not wanting to be recognized resonates with me. Similarly, the overwhelming majority of service members don’t seek recognition. The strange thing is that sometimes when someone thanks us for serving, on the outside we are grateful for their appreciation, but internally we don’t know how to react. Many of the soldiers with whom I’ve spoken don’t really even know what to say in return. Usually, I respond with a simple “thank you.” It’s an awkward conversation that has been repeated many times, yet the awkwardness remains. These people are consciously trying to close the gap, and I don’t seem to have an appropriate way to respond to their kind gesture. I would ask any civilian who reads this that your gratitude is very appreciated, it’s just hard to respond without sounding arrogant.

The overuse of the term “hero” has also done great damage to the military. The overwhelming hyperbole of today’s political rhetoric has turned otherwise well-meaning compliments into buzzwords. Not everyone is a hero. Simply putting on a uniform does not make one person better than another. Military heroes are a select group. They are the wounded, the psychologically damaged, and most of all, the dead. I would even venture to say that many of those people would not consider themselves heroes, although they are the ones that have sacrificed the most. The clerk that sits in the air-conditioning for a yearlong tour and the wounded combat soldier that has bled on the streets of Baghdad are not the same. While everyone’s service is needed and appreciated, the public needs to understand that the vast majority of service members do not consider themselves heroes, and are actually repulsed by the idea of being labeled as such. Please don’t throw that term around; reserve it for those that have earned it. In doing so, you will show far more understanding than you could ever imagine.

The “hero” problem is not just an external issue, however. There is an overwhelming, off-putting “hero complex” that today’s veterans have developed which has also widened the gap. Task and Purpose recently published a spoof video in which a veteran explains the importance of “veterans only” parking spots. While the video is obviously made to be funny, the over-the-top nature of the veteran’s argument is a statement on the desire to be put on a pedestal embraced by many military members and veterans. Simply put, many veterans have bought into their own hype, and it is widening the civil-military divide far more than anything said or done by our civilian counterparts. Most of these people are younger soldiers who have done little to prove themselves besides attending basic training and putting on a uniform every day. In fact, the word “hero,” when said sarcastically, is now often used as an insult in military circles.

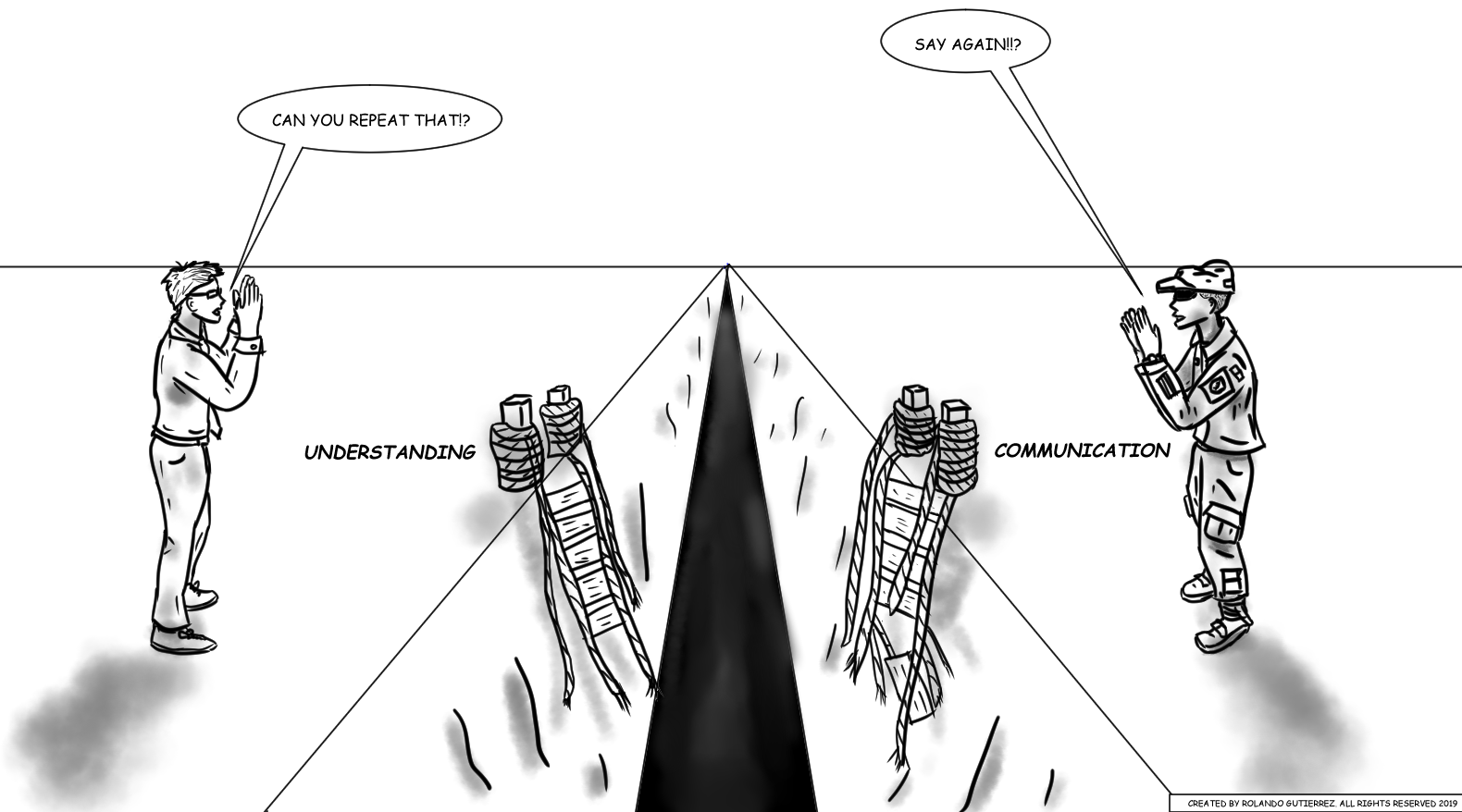

Both sides of the civil-military chasm are responsible for its expansion. Civilians offering flippant support to the military is just as insulting as the all-too-often air of superiority taken on by military members and veterans. Anyone serious about closing the civil-military gap must understand that military members, more often than not, are doing jobs similar to a civilian office job. Granted, there are dangerous times for some. For the majority however, with the exception of an hour of physical training in the morning, military members work a nine-to-five job. Additionally, there are heroes on both sides of the civil-military gap. The young soldier who exposes himself to danger to help a fellow soldier is a hero. The grocery store manager that spends her weekends serving at a soup kitchen is also a hero. Simply put, the military community does not have a monopoly on heroism.We military members and veterans need to understand that success in our field means that those on the home-front do not need to worry about the dangers abroad. The fact that most Americans in their daily lives need not worry about Al Qaeda, ISIS, and their affiliates means that we have accomplished our mission. Likewise, civilians could do a lot of good by simply trying to comprehend the very basics of what military life actually is. Voting, and understanding what they are voting for, is also critically important. Doing their part to ensure that military lives are spent frugally is one of the most important, if not the most important, acts an American citizen can do. By having an open dialogue and understanding their respective roles in society, civilians and military members/veterans can finally begin to bridge the chasm that has split our nation since the war began in 2001.

Special thanks to Rolando Gutierrez for creating the image for this article! You can find his work at https://blackhorsescomic.wordpress.com/

Sources:

https://www.census.gov

https://www.taskandpurpose.com (YouTube channel)

https://www.armstrongeconomics.com/us-population-1776-date/

https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2018/03/20/2-77-million-service-members-have-served-on-5-4-million-deployments-since-911-infographic/#289fd71450db

Leave a comment