Horse, Saddle, and Rider: Creating Trust through Non-Tactical Operations

Trust is one of the greatest assets that an organization possesses. As I discussed in my last two “Weaponizing Trust” articles, the levels of trust that run horizontally and vertically through a unit are positively correlated to its combat effectiveness. In my time with the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment (Blackhorse), I saw how the high levels of trust between commanders at all echelons allowed the unit to change missions and task organizations in-stride, something that is difficult for most other units. This is not, however, an indictment of other formations. Because the Blackhorse fights ten National Training Center (NTC) rotations each year, the commanders at each echelon are able to make mistakes, conduct after-action reviews (AAR), and act on the lessons learned every month. I consider myself absolutely blessed to have been in a command climate that conducted and valued in-depth AARs, allowed for honest mistakes, and let me work through the lessons that I learned in the next fight. Granted, not every unit has the same opportunities as the Blackhorse. However, developing a healthy trust-based culture is not contingent upon tactical operations. Leaders of all types of formations can still develop a climate within the formation that allows for leaders to make mistakes, learn lessons, and practice what they have learned without leaving the motor pool.

This process can happen in two steps. First, members of the formation must have an appreciation for the unit of which they are a part, and how they fit into that unit’s success. Second, to cultivate the desired culture, leaders must get repetitions in military operations where they can build trust horizontally and vertically throughout the formation. There is one activity common to all military formations where the same lessons can be learned: maintenance. Maintaining the unit’s vehicles and weapon systems, as well as its personnel through administrative and legal actions allows a unit to cultivate a culture where leaders at all echelons can learn, grow, and build bonds of trust which will ultimately translate to the battlefield.

DEFINING THE CULTURE

When I took command of H Company, 2nd Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry, it was like stepping on a treadmill that was turned up to full speed. The healthy command relationships that I’ve described in my last two pieces were already well-established. The bar of excellence had been set high by my fellow commanders and I needed to rise to their level if I was going to be successful. The command culture based on trust and the repetitions provided by the OPFOR mission made this a natural progression for all new commanders.

A little over a year later, I took command of Headquarters and Headquarters Troop, 1st Squadron. The Squadron Commander at the time, then Lieutenant Colonel Chris Danbeck (who has since been promoted) told me that from day one, that my “trust bucket” was full, and it was important to keep it that way. The goal wasn’t a zero-defect organization, but instead an environment where mistakes could be made (outside of illegality or immorality) and growth through learning could happen. As commanders in that organization, we also had an enormous say in the direction of how things were done. I had more autonomy than I ever thought I would. In fact, Colonel Danbeck once said that, “if you are uncomfortable with the amount of leash you are giving your subordinates, you are probably doing things right.” Not intervening before we could make mistakes was probably very difficult for him, but he knew the importance of the learning cycle. This philosophy paid dividends when it came to developing leadership seasoned, confident leadership that was able to quickly make decisions and provide informed recommendations in tactical operations.

Lieutenant Colonel Ryan Kranc, who served as an Operations Officer at the Squadron and Regimental level in Blackhorse and later went on to command a Cavalry Squadron, provided me great insight into the process of building this culture. He said that ultimately, his goal was to foster a culture in which when he “grabbed the TC override,” to use a tanker phrase, his subordinates knew that he was stepping in for a good reason even if he did not have time to explain why. He wanted them to understand that his goal was never to micromanage, but given his amount of experience in comparison to his subordinate commanders, sometimes it was necessary to pull back on the reins to avoid a certain outcome. He broke down his process into two main parts: defining roles and defining excellence, both collectively as a unit as well as for the individual soldier. Helping the individual soldiers understand where they fit into the unit, and how excellence in their particular role ultimately impacts the unit’s overall success, is of the greatest import. To do this however, one must understand they do not own the unit; they are merely stewards of the unit’s history, the unit’s present mission, and posturing the unit for future success. Many units do this very well because the United States Army’s Regimental System affords them a ready-made unit legacies upon which to draw. Soldiers joining these units are indoctrinated in the history and achievements of their forebears, giving them a bar of excellence for which to strive.

In my first assignment as an officer, for a time I was the newest (definitely not the youngest) Second Lieutenant in the battalion. My battalion’s motto was “‘til the last round,” which was a quote from the Color Sergeant at the Battle of Murfreesboro during the American Civil War. Because of this, as the battalion’s newest Second Lieutenant, I had to carry a deactivated 7.62mm round with the regimental motto etched into it. It had to go everywhere with me, including physical training and field operations. It had to be in the “utmost state of repair,” at all times, and could be inspected at any time by the Battalion Commander or Battalion Command Sergeant Major. I had to memorize the story of the “last round” and present it in front of the Battalion’s senior leaders at a Hail and Farewell celebration. There was a similar requirement for the youngest enlisted soldier in the battalion. Likewise, 1st Squadron, 11th ACR has a similar tradition. The squadron has a statue called “Trooper of the Plains,” which the newest Lieutenant must to bring to all official unit functions. He or she is required to guard it at all times at these functions, and to ensure that the Trooper never goes thirsty. To pass off the Trooper, the young officer must recite the unit’s history to the satisfaction of the Squadron leadership.

These are just two examples in my own career of organizations indoctrinating their newest personnel into the units’ proud history. Many units in the United States Army have similar traditions or rites of passage (Prop Blast or Mungadai for example), and they are a critical part of building a combat-effective team. LTC Kranc mentioned Spur Rides as a cavalry alternative, which allow mixed-rank squads to demonstrate understanding of history, as well as proficiency in basic soldier skills. After having passing off the “Last Round,” I understood the long and proud history of the Regiment. It gave me an appreciation for my small piece of that history as a platoon leader, company executive officer, and battalion assistant operations officer. To this day I wear that patch, instead of others I could wear, on my right arm because of what my part of the unit’s history means to me. This pride and understanding served as motivation to be a steward of the unit in which I was serving, and I worked as hard as possible to be worthy of the unit of which I was a part.

HORSE AND SADDLE

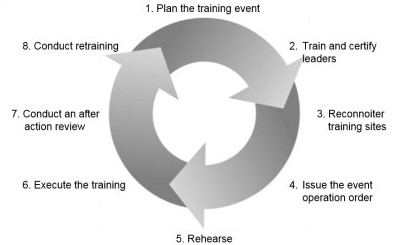

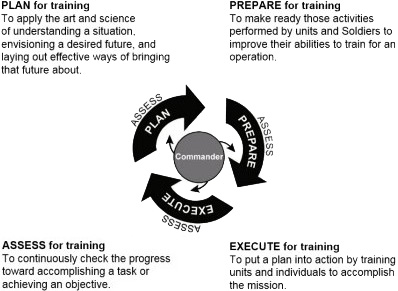

An organization’s tie to history is not limited to dates and battle honors. The old cavalry priorities of work, “horse, saddle, and rider” is still very much alive today and provides a unit the opportunity to build trust through all echelons. Lieutenant Colonel Kevin Black, a current Battalion Commander and Blackhorse alum, explained that the operationalization of non-tactical unit functions is an essential method for getting repetitions in going through the Eight Step Training Model and Troop Leading Procedures. Command Maintenance, he said, must be treated like any other training event, including publishing it on the training calendar. Then and only then can it be fully operationalized and provide the repetitions necessary to build trust throughout the organization.

Motor Pool Monday is a universally understood concept throughout the mechanized and motorized formations in the US Army. It gives the soldiers time to get hands-on experience with their vehicles, and imbues a sense of ownership of the equipment with which they are expected to fight. Proper and thorough maintenance of a unit’s vehicular fleet and weapon systems is not only crucial for a unit’s readiness, but it also allows leaders at all echelons to get repetitions in going through the full operations process, which ultimately brings to the fore the leadership’s decision-making ability as well as their self-awareness and maturity. It also provides junior officers the opportunity to brief the battalion/squadron commander and/or the executive officer on their plan, giving them “facetime” with senior leadership. Services in-briefs and out-briefs give platoon leadership a high-stakes repetition in briefing a plan (service in-brief), preparation (assembling the service kits and doing the requisite paperwork), execution (conducting services), and conduct an after-action review (services out-brief).

RIDER

In several of the units in which I have served, the service in-briefs and out-briefs also included all personnel readiness metrics. These metrics ensure that the unit’s personnel are ready to deploy alongside the vehicles they crew and maintain. While personnel readiness maintenance (immunizations, life insurance update, drivers’ licenses, weapons qualifications, etc.) is not quite the most glamorous subject, any unit with non-deployable soldiers occupying slots on their roster is sure to have issues when it comes time to deploy, whether to the National Training Center, Joint Readiness Training Center, Joint Multinational Readiness Center, or to combat. By including these metrics with the maintenance of critical equipment, units are giving leaders at every echelon the opportunity operationalize all aspects of their units’ readiness and providing them yet another repetition in performing the entire operations process. Outside of turning yellow (or God forbid red) bubbles on a PowerPoint slide green, these personnel actions show that the unit’s leadership understands the full scope of their duties, and produces plans to ensure all necessary metrics are planned for and standards for deployability are met.

Since I commanded in the Blackhorse, my previous writings have focused entirely on the tactical implications of trust in a formation. Administrative functions however touch far more of the formation on a daily basis than tactical situations, especially in non-OPFOR units. These personnel actions (promotions, awards, reenlistments, leave and pass forms, discharges, etc.) are a direct way to foster trust throughout the organization. Timely promotions show the formation that the unit leadership cares about their advancement. One of my favorite actions as a commander was to laterally promote a soldier from Specialist to Corporal. It shows to the soldier and the formation that he or she has impressed the unit leadership with their demonstrated leadership ability and will therefore wear the stripes of a Non-Commissioned Officer, the universally understood symbol of authority that transcends service branch and even nations. It’s a tangible symbol of the trust that the unit’s leadership is placing in the soldier. The fact that it’s an optional promotion, outside of the standard progression, makes the rank of Corporal even more extraordinary.

The same goes for awards and other positive administrative actions. Giving awards to worthy soldiers is a way to recognize them in front of their peers, and also shows soldiers that the leadership cares about their career progression. Taking the time to write awards for soldiers shows them that they can trust in their leadership’s loyalty to them and their careers, which will foster trust and loyalty to the unit and chain of command in return. It also provides an example to the soldiers of what is expected of them when they become leaders. Other actions, like leave forms, the validation of documents so soldiers can get family housing, and approving their attendance to army schools (Airborne, Air Assault, Mortar Leader, etc.) fosters the same level of trust and loyalty that will transcend the administrative action realm and pay dividends in the battlefield. How subordinate leaders conduct their administrative actions tells leaders at higher echelons, again, that they understand the full scope of their duties. This increases the level of trust within the formation as well. Likewise, if soldiers know that you are ready and willing to reward them for the good things that they do, legal actions for the bad things take on a much greater meaning within the formation.

When I first took command of H Company in April 2016, there was a slight morale problem. The company had (the typical) ten percent of our ranks that were always getting in trouble, but with no concrete legal results. In some cases, the process had been started, but was still going through vetting. With the help of the new company First Sergeant, we made strict legal discipline our priority. We needed to stem the tide of misconduct in our ranks. I thought that this would result in a temporary drop in morale because of our heavy-handed pursuit of legal actions. To my surprise, after the first three cases (two were courts martial for drug use, and one court martial for a soldier being absent without leave) morale improved dramatically. It became apparently clear to the company that the chain of command was dealing swiftly with the misconduct. As anyone that has commanded can attest, this process wasn’t ongoing when I handed the guidon off to my successor. However, with the first few cases, I learned a stark lesson about the value to legal action.

LTC Black also commented on the importance of legal actions within a formation. He said that, for him, each Article 15 (non-judicial punishment) became a leadership professional development (LPD) session with the junior leaders. He demonstrated how the consistent application of legal authority was a maintenance process, just as much as taking oil samples or conducting preventative maintenance checks and services (PMCS). I personally never fully recognized that link. I did however, as most commanders do, allow the soldier’s entire chain of command to give recommendations on the sanctions imposed, if the soldier was found guilty. I started from the most junior leader, normally the Squad Leader, and ended at the First Sergeant. I wanted everyone to know that they had a direct say into what was going to happen to their soldier. Once I announced the punishment, I would then turn to the chain of command, and in front of the soldier define my expectations for all of them. I told them that the soldier was not to be ostracized, teased, or mistreated by either the leadership or the soldier’s peers. Once the punishment was finished, I expected the soldier and the leadership to go back to operations as normal. I would tell them that we are a family, and we pick our people up, dust them off, and continue the mission. My ultimate goal was to show the soldier that they were being punished for their actions, not because they were bad soldiers. I wanted them to know that they did not hold any lesser value for having gone through this process.

CONCLUSION

We were truly lucky in the Blackhorse to have the opportunity, in a tactical environment, to build the strong bonds of trust which I have discussed previously. Unfortunately, not all units get that opportunity. However by reaching back to our history and operationalizing everyday processes, every unit has the ability to build the same kinds of relationships that we held so dear in the OPFOR. As leaders, it is our most important duty to ensure that all of our weapon systems, including our people, are maintained to the highest standard possible. By adhering to the old cavalry priorities of work of horse, saddle, and rider, and using maintenance as the method to build trust throughout the formation, every unit has the potential to forge the relationships necessary for success on the battlefield.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks to COL Chris Danbeck, LTC Ryan Kranc, LTC Kevin Black, LTC(R) John Cross, and CSM(R) Mike Evans for the assistance they provided me as I worked through this article. The military is a wonderful organization in which relationships remain strong, regardless of time or physical distance. Thank you for your time and support!

Yet another quality read! Well done indeed.

Til the Last Round Vanguard! Again, looking forward to the next one.

LikeLike